Basic ACL Information

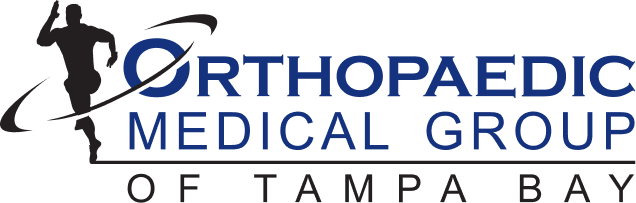

The anterior cruciate ligament, ACL, is one of the 4 major stabilizing ligaments of the knee. The ACL is located in the central aspect, (intercondylar notch), of the knee and acts as a restraint to anterior tibial translation and rotation. In layman’s terms, this means that the ACL keeps the tibia (shin bone) from shifting forward, or twisting out from under the femur (thigh bone) during activity. This ligament connects the femur and tibia to restrain this motion, but can be injured with either contact or non-contact type twisting injuries to the knee.

ACL injuries account for about half of all reported knee injuries with nearly 400,000 ACL reconstructions performed in the US annually! Female athletes are about 4-5x more likely than males to sustain an ACL injury. While the majority of these injuries happen during sport, they can occur with work injuries, motor vehicle accidents, and injury during falls or other non-sporting events.

Other injuries to the knee can occur with an ACL tear and these include meniscus tears, cartilage damage, or other ligament injuries such as the PCL, MCL, or LCL/posterolateral corner.

What does an ACL injury feel like?

When an ACL injury occurs, the patient typically reports a sharp pain associated with a “popping” sensation in the knee followed by a buckling or giving way. The knee typically swells within the first 24 hours. This swelling usually alleviates within a few days to weeks with ice, rest and range of motion exercises and the pain also goes down or away. It is not uncommon for patients to report feeling nearly normal within a few weeks after injury, especially with an isolated ACL tear.

Normal walking is also possible with an ACL tear as the ACL is only necessary during pivoting or rotating movements of the knee. You could walk in a straight line forever without an ACL, but when you go to stop, turn and pivot with your toes in a different direction, that is when the ACL comes into play and in an ACL deficient knee, the knee may pivot or give way.

The long term consequence of an ACL deficient knee is the development of early arthritis in the knee related to cartilage damage from these repeat episodes of giving out.

Diagnosing an ACL Injury

Diagnosing an ACL Injury

The diagnosis of an ACL tear begins with a history of the injury and symptoms as well as a good physical exam which can detect the instability in the knee. X-rays are helpful to look for other pathology, and sometimes there are radiographic signs that can hint towards an ACL injury. The diagnosis is confirmed on MRI which is mostly important for surgical planning purposes and to look for other associated injuries.

Options After Diagnosis

While awaiting the MRI results, initial therapy can begin to help decrease swelling and pain, as well as regain motion and re-activate the quadriceps muscle. After knee injury, the quadriceps muscle shuts down and needs to be “woken up” to allow for proper functional recovery.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed on MRI, surgery is usually recommended. Non-operative treatment with bracing and physical therapy can be considered, but is only indicated for older, more sedentary individuals due to the high risk of recurrent instability leading to further damage to meniscal or chondral tissue in the knee. For these reasons, in younger, active patients who are healthy enough for surgery, we recommend proceeding with either ACL repair for certain types of acute tears or in most cases, ACL reconstruction using a tendon graft.

Preparing a quadriceps tendon graft

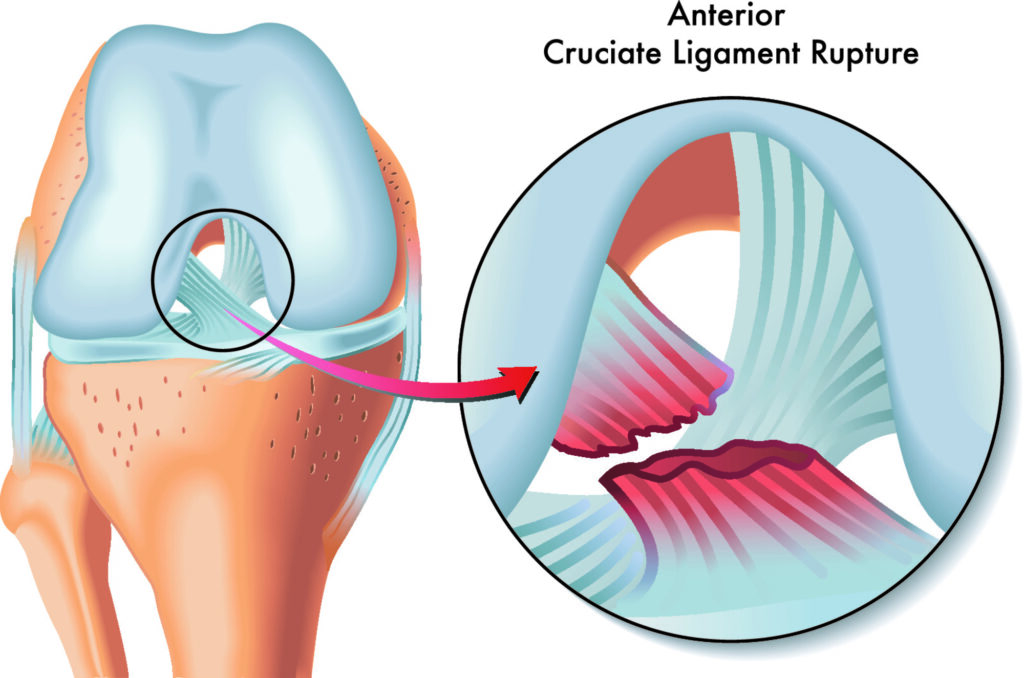

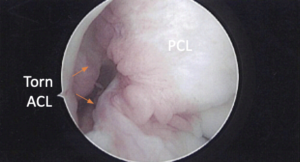

The ACL is within the knee joint and is bathed in synovial fluid which actually works to prevent healing of the ACL tear, and also works against our ability to directly repair the ligament when torn. For a few types of tears, where the ligament tears off of the bone, rather than mid-substance, there are arthroscopic repair techniques to attach the ligament back to the bone. In the vast majority of cases however, the tear pattern is not amenable to this, and ACL reconstruction (making a new ACL) is recommended.

Autograft tendon (from you) taken from either the patellar tendon, hamstring tendons, or quadriceps tendon are the typical sources used for ACL reconstruction. Another option is to use an allograft tendon (cadaver) to recreate the ligament. Allograft tendons have been associated with higher re-tear rates, especially in young athletes, and are thus typically recommended for lower demand patients.

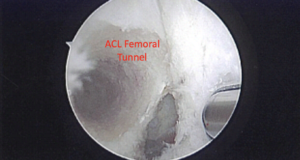

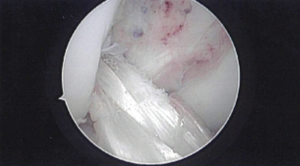

Arthroscopic images of ACL Injury and Reconstruction Process

For autograft tendon choices, most clinical and biomechanical studies show similar results with all 3 of these graft options and so the decision on which graft to use often comes down to surgeon or patient preference. A consultation and discussion with your doctor about which graft choice is right for you based on your goals and preferences will help make this decision.

Hamstring Autograft

ACL Injury Recovery

Recovery after ACL surgery requires extensive rehabilitation with physical therapy. With just an ACL reconstruction, you will likely be on crutches for 1-2 weeks and then walking with a brace after this for 4-6 weeks before discontinuing the brace. Your return to sport however is likely 9 months away as it takes this long to allow for graft maturation and proper rebuilding of strength and neuromuscular control to protect the healing ligament before returning to play.

Any additional procedures that need to be performed with your ACL surgery such as meniscal repairs, cartilage repair, or other ligament reconstructions may increase your recovery from 9-12 months or more.

While it is a long road, the success of ACL reconstruction surgery is high with nearly 90% of patients returning to pre-injury level of activity. Long term maintenance of muscle strength and conditioning is important and overall re-tear rates are low.

Looking for a consultation for your ACL Injury? Our sports medicine specialists, Drs. Becker, Sando, and Watson are well trained in all varieties of ACL surgery from primary repairs to complex revision reconstructions using all graft types.

Dr. Mark Sando is an internationally recognized orthopaedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine, arthroscopy and injuries of the shoulder, knee and hip. He earned his medical degree from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine and completed residency at the University of Maryland Medical Center and R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center. After residency, Dr. Sando went on to complete subspecialized training in Sports Medicine as a fellow at the prestigious Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic in Los Angeles, CA under the direction of Dr. Neal ElAttrache. He has worked with numerous college athletic programs and professional teams including the world champion Los Angeles Kings, Los Angeles Lakers, Los Angeles Dodgers, and Los Angeles Sparks. Dr. Sando has been with the Orthopaedic Medical Group of Tampa Bay since 2015. Full Bio